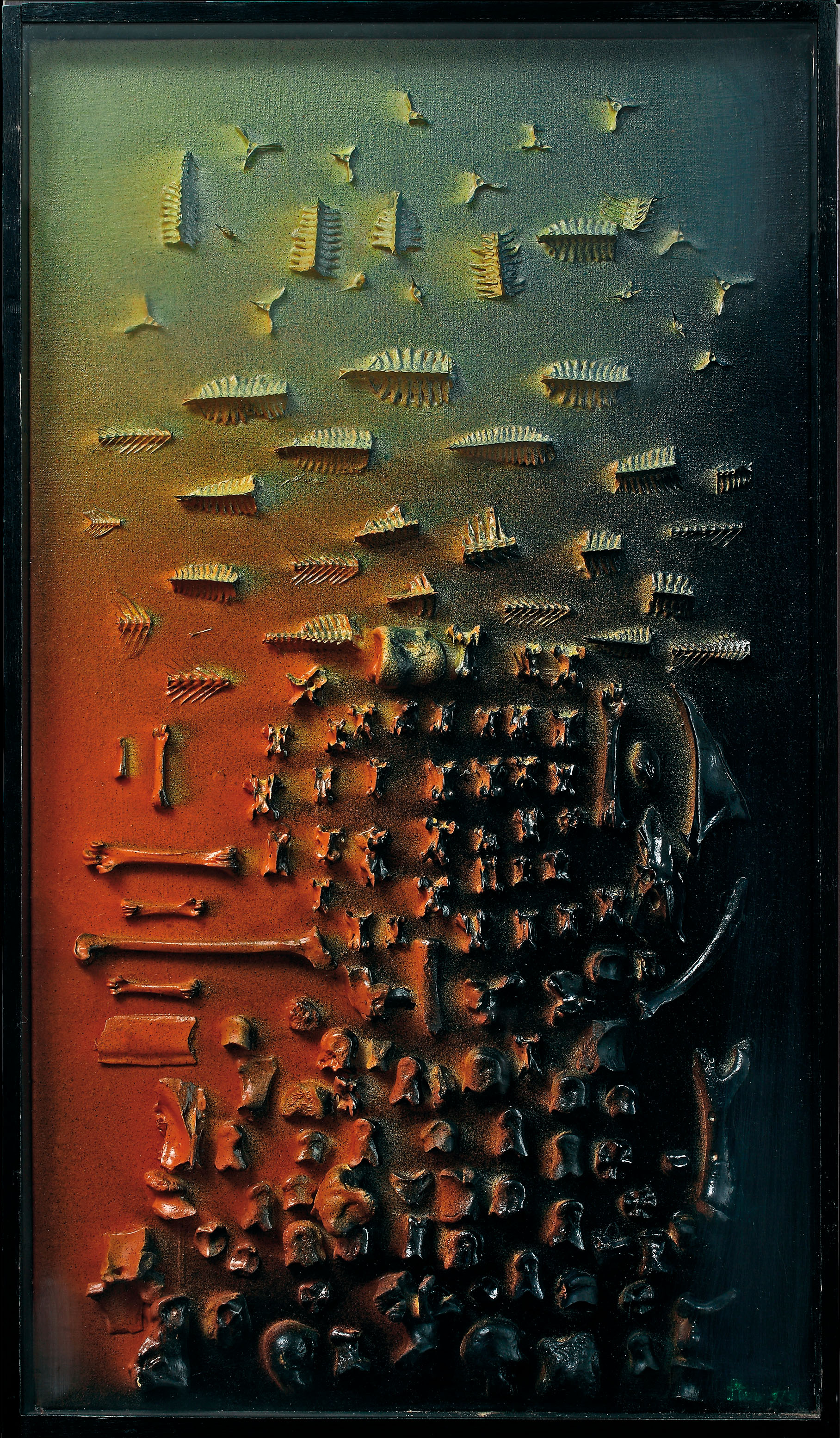

1973, oil on canvas, bones, 90 cm x 50 cm,

average looking time: 17 sec

I cannot die as I have died once already.

J. Stern about having experienced his own execution in 1941

Jonasz Stern is a well-known artist in the Polish cultural environment. He was born in 1904 in Kałusz near Stanisławów (current territory of Ukraine), died in 1988 in Zakopane. Stern graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków. He was searching for his own artistic path for quite a long time. What determined his painting was, among others, his cirrucular opposition towards academic art. His pre-war works seemed to lie between cubism, surrealism, and abstract art. At the time of war, he was persecuted for his Jewish origins – he spent a few months imprisoned in a death camp in Bełżec. These experiences turned out to have great impact on his post-war art. 1941 was the year when Stern almost died – he experienced execution, but miraculously survived. After the war, he turned to surrealist art and social realism, understood in his own way. With Kantor and Nowosielski, he belonged to the greatest representatives of the Kraków school. In his artistic career, he experimented with various techniques, incl. monotyping, watercolour painting, gouache, decalcomania and collage.

„The Moment of Light” belongs to Stern’s later works, which perfectly shows his technique. The artist arranged fish skin and bones, and the bones of small animals, into abstract, almost surreal compositions. He began creating such works in 1965. The painter was well-known for his passion for fishing, which used to see a “deep experience”. In order to explain one of his compositions, he wrote “A comment on pictures about fish”. “Predatory pikes, Predatory zanders, Cunning chubs, Lazy tenches, Careless bleaks, Wandering eels, Fat carps, Cowardly gudgeons, Lively barbels, Secretive burbots, Harmful perches, Hardworking nases and others… Prolong their very existence in silence”. His art contains clear references to transience of life, destroying and saving of what has remained”.

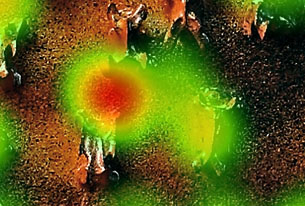

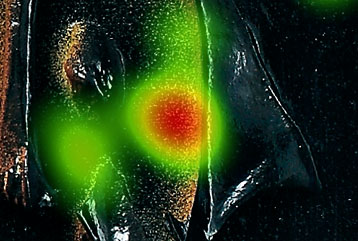

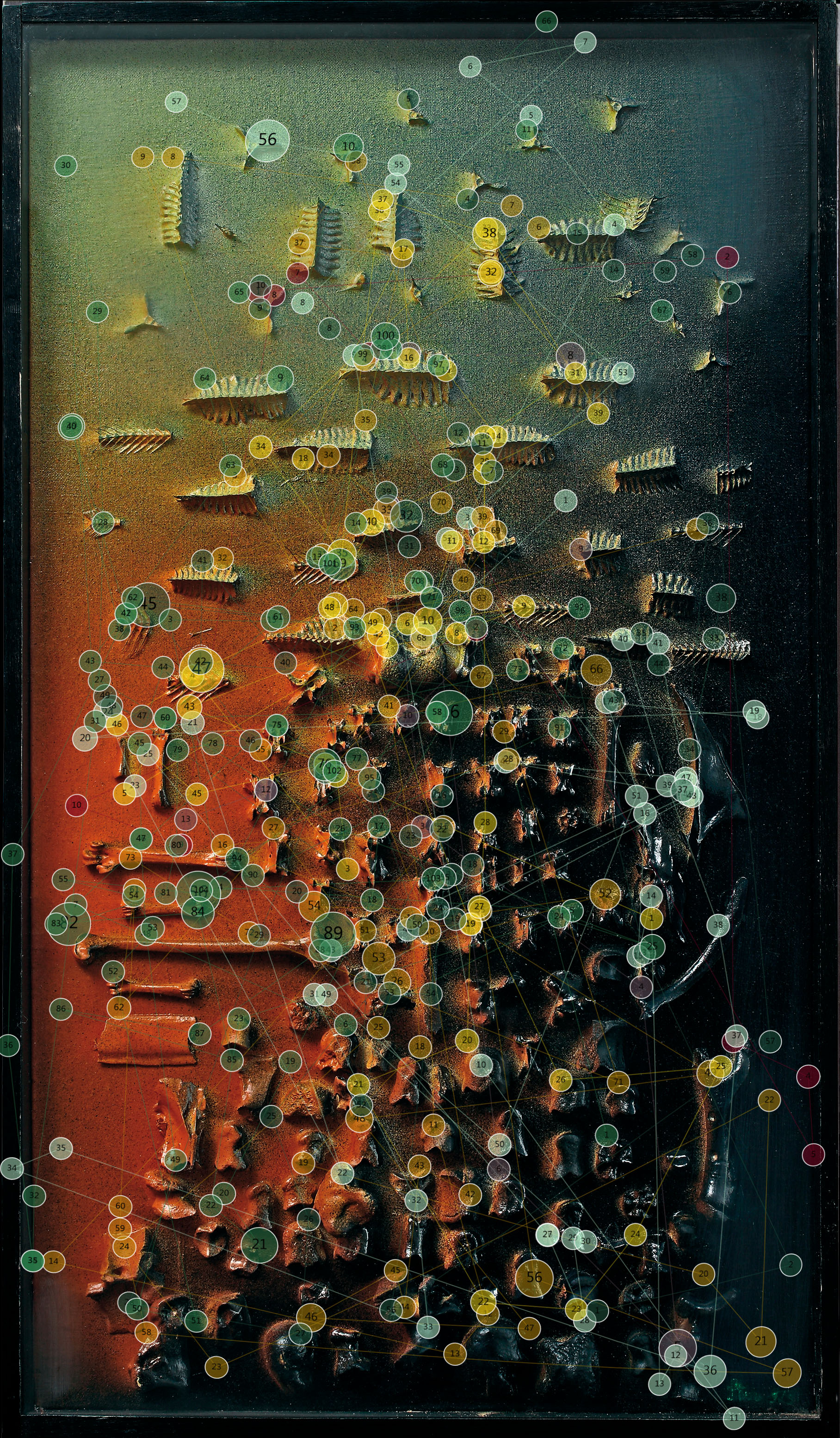

The participants of our experiment tended to focus on particular elements, following the sophisticated structure composed of single fragments of bones. On the heat map we can see the viewers’ preference to stop their eyes in the upper parts of the picture, abound in smaller elements and brighter colours than the lower parts. It’s worth noting the three-dimensionality of the work, which often made the participants change their viewing angle, resulting in a completely new frame, impossible to capture in one photograph.

Each of us looks at the picture in a different way!

Previous

Tadeusz Brzozowski “Favours”

- How to use the guide

- Andrzej Wróblewski “Shooting I, Execution”

- Stanisław Borysowski “K. B. Graphic”

- Tadeusz Dominik “Composition”

- Zbigniew Makowski “Still Life”

- Anna A. Güntner “High School Graduates”

- Zdzisław Beksiński “Untitled”

- Tadeusz Kantor “Multipart – An Umbrella”

- Tadeusz Brzozowski “Favours”

- Jonasz Stern “The Moment of Light”

- Łukasz Korolkiewicz “Dwellers of Sodom”

- Interviews