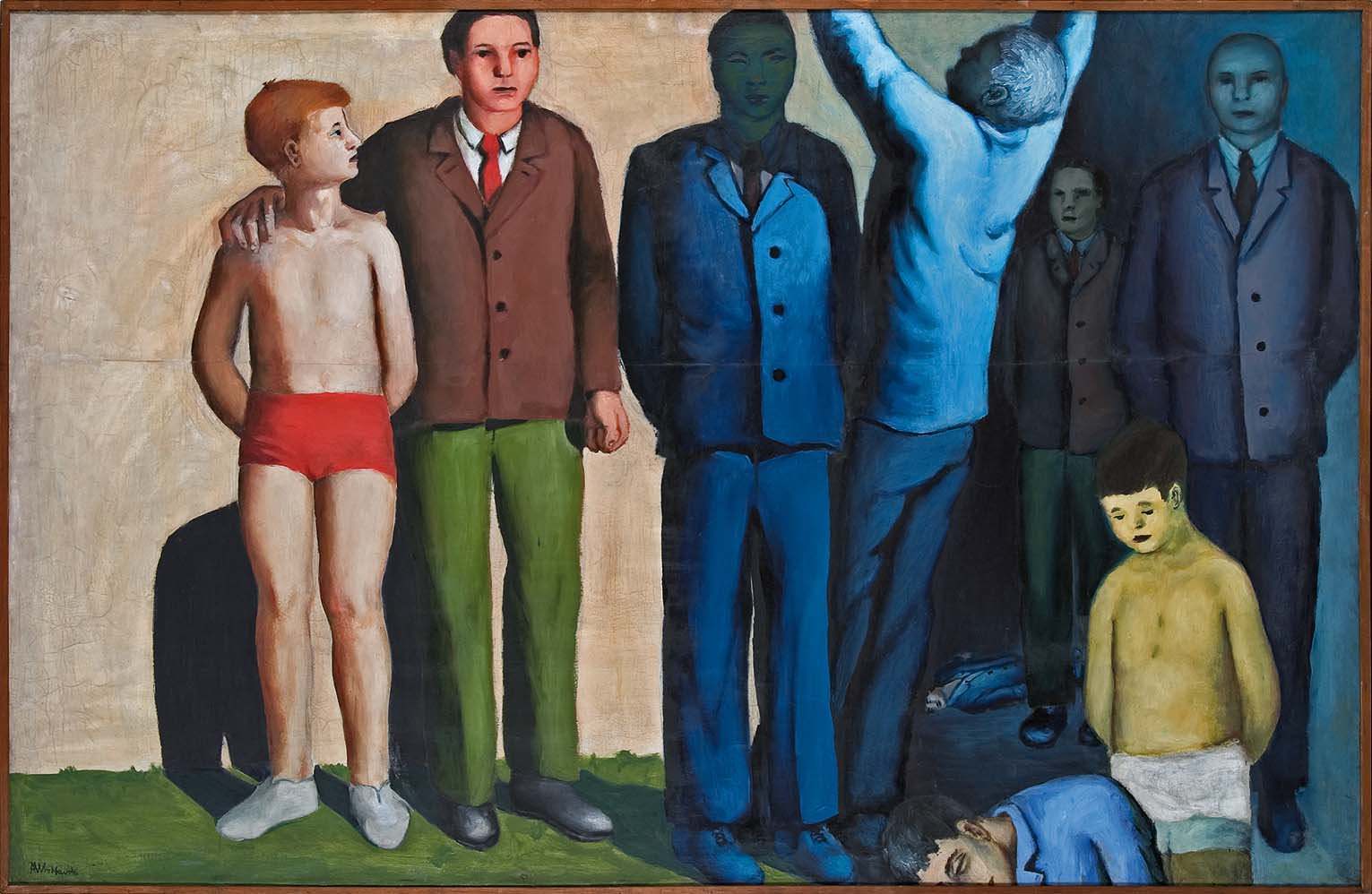

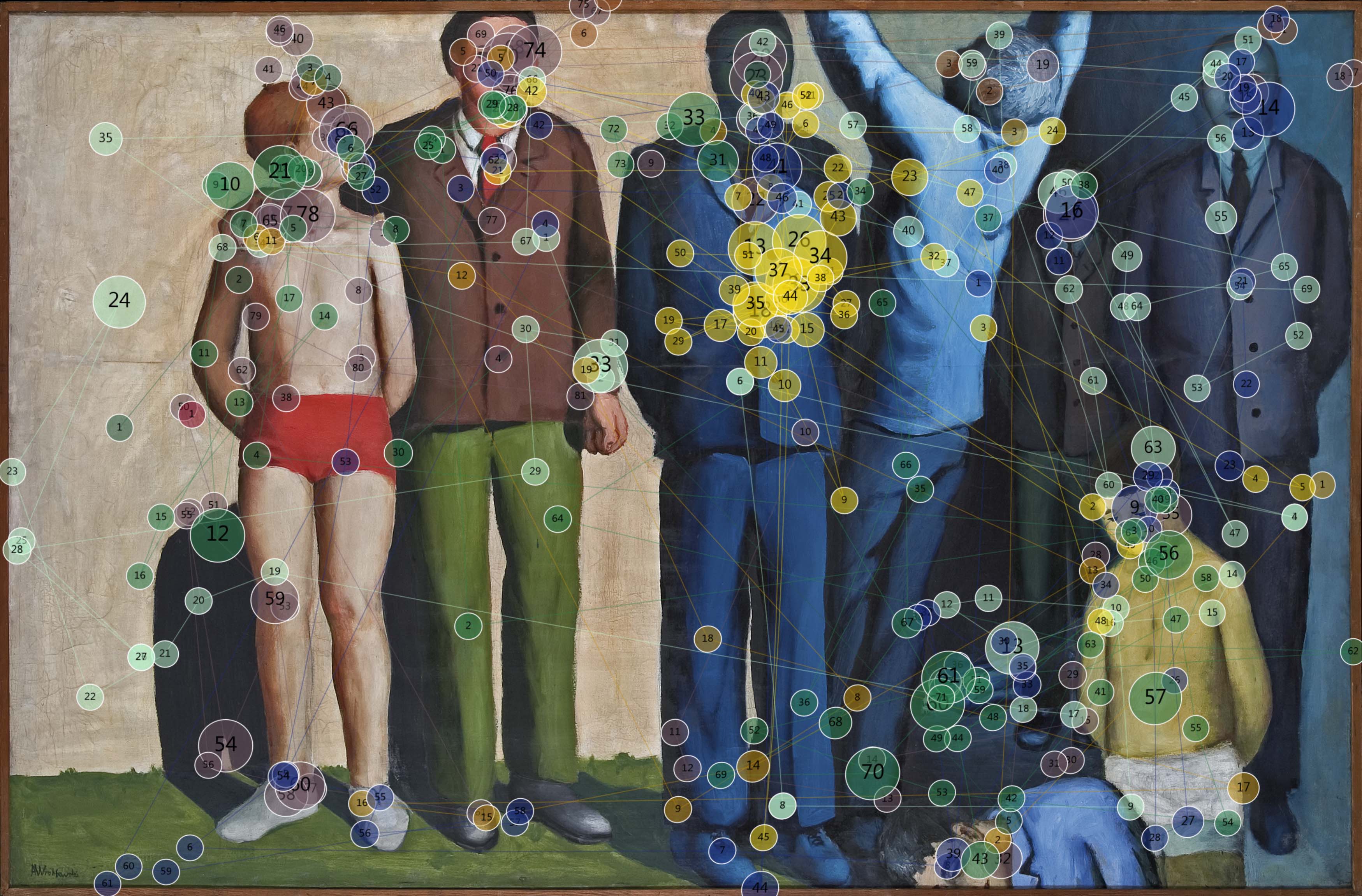

1948, oil on canvas, 127 cm x 198 cm,

average looking time: 17,78 sec.

– Why do you paint all the dead ones in blue?

– I’ve got a whole tube of Parisian blue, which, as you know, is really efficient.A. Wajda to A. Wróblewski

Andrzej Wróblewski is one of the most recognisable Polish 20th century painters. He was born in 1927 in Vilnius, died in 1957 in Zakopane. Graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków. In his works, he followed a well-defined ideological program. According to Wróblewski, painting should be communicative and understandable for everyone. The artist wrote that he wanted his art to be “possibly unchanged, objective, photographic, reflecting common seeing and imagination of the working masses”. His attitude towards socialist realism was changing as the years and the growing regime went by. The painter became well-known only after his death, especially thanks to his famous execution series. Andrzej Wajda wrote once that “[…] Wróblewski is the only real post-war original Polish painter. Perhaps there are better, but he’s the one who has expressed himself completely and – just like great artists from the past – gave his life for art.”

Wróblewski used to comment on his art: “I tried to avoid any style of mine and aesthetics which I should stick to for every single idea”. Thanks to such attitude, the artist has developed his own, easily recognisable formula. The series of executions was inspired by propaganda photographs showing a street execution done in 1939 in Bydgoszcz. The Hitlerite propaganda used to call this event a “bloody Bydgoszcz Sunday”. A unique, yet full of verismo and fantasy, way of presenting the event, is sometimes referred to as “new realism” or simply “the art of fact”.

The details above present mostly faces which are shaped in a way typical for Wróblewski’s paintings. What distinguished him was a “concise” manner of drawing; his characters used to be rather stocky, of slightly Latin features. This way of painting probably resulted from Wróblewski’s taste in Mexican wall painters, such as Diego Rivera, Renato Guttuso, Andre Fougeron. We know about his fascination with Mexican painters in 1946. Another important element are figures of boys, often presented as observers and probably future victims. Their appearance might be associated with trauma the artist experienced seeing his father’s death in 1941, when the Nazis were searching his family house in Vilnius.

Each of us looks at the picture in a different way!

Previous

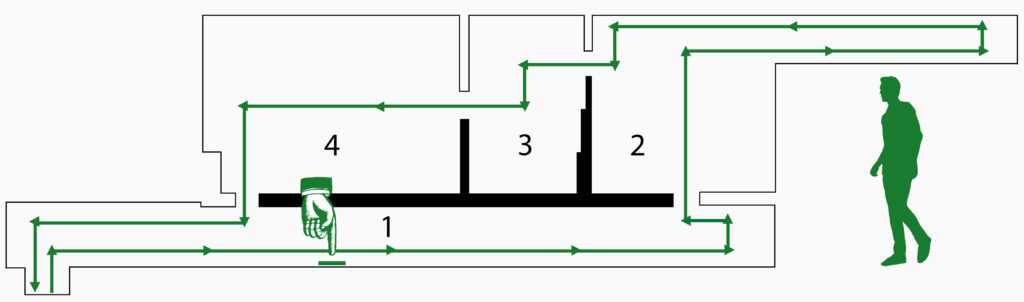

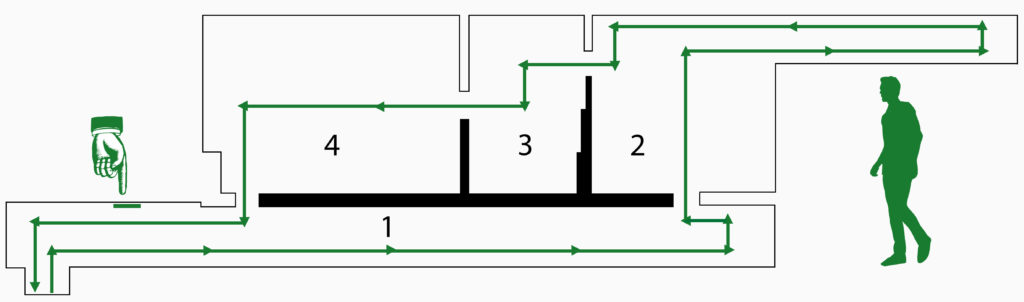

How to use the guide

Site map

- How to use the guide

- Andrzej Wróblewski “Shooting I, Execution”

- Stanisław Borysowski “K. B. Graphic”

- Tadeusz Dominik “Composition”

- Zbigniew Makowski “Still Life”

- Anna A. Güntner “High School Graduates”

- Zdzisław Beksiński “Untitled”

- Tadeusz Kantor “Multipart – An Umbrella”

- Tadeusz Brzozowski “Favours”

- Jonasz Stern “The Moment of Light”

- Łukasz Korolkiewicz “Dwellers of Sodom”

- Interviews

PROJECT REALISED AS PART OF THE KUYAVIAN-POMERANIAN VOIVODSHIP MARSHALL SCHOLARSHIP

content & graphic design: Łukasz Kędziora | art collection photographs: Krzysztof Deczyński | translation and proofreading by Martyna Kowalska